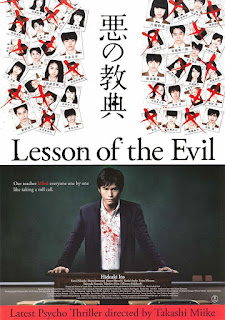

Envied by his colleges and loved by his students, English teacher Seiji Hasumi is the most popular teacher at his high school, however one of Hasumi’s fellow teachers, Tsurii, isn’t as enamored with Hasumi as everyone else is, finding something suspicious about his demeanor. Tsurii’s suspicions aren’t without warrant, as Hasumi’s friendly and outgoing personality mask a murderous psychopath who’s true nature surfaces after Hasumi uncovers a bullying problem within the school and several trusting students confiding in him about another student being sexually abused by a gym teacher, forcing Hasumi to put an end to the school's troubles in his own unique manner.

Although much different in tone, its difficult to not compare Lesson of the Evil (Aku no Kyoten, 悪の教典) to Audition in the sense that, much like Miike’s breakout horror film, Lesson of the Evil finds Miike taking his time, slowly building up to an utterly jaw-dropping conclusion, dropping hints of what’s in store along the way. Essentially split up into three sections, the film begins with Miike establishing Hasumi’s reputation within the school, his rapport with the students and also spending some time with the students themselves, Miike’s reasoning coming into play later on. What’s especially interesting about the films first act is Miike’s early revealing of Hasumi’s true personality with his engaging in a sexual relationship with a student, setting in motion the direction the film will eventually take. Its during the mid-section of the film where things begin to grow darker in tone with Miike digging into Hasumi’s past and literally getting into his psyche, giving way to some memorable surrealistic sequences. Its during the final third where the film takes its most drastic turn, with Hasumi putting his warped plan of cleaning up the school into action, leading to one of the most barbaric bloodbaths ever committed to film. What’s more, Miike manages to sprinkle in bits of his thoroughly morbid sense of humor at certain points during Hasumi’s indiscriminate massacring of teenagers, namely Hasumi killing to the catchy tune of “Mack the Knife”, a decision that’s sure to take some of the most jaded horror viewers back a bit.

Although the film gives a fairly in-depth presentation of Hasumi’s past, the same year the film was released a TV mini-series prequel was produced, appropriately titled Lesson of the Evil: Prologue (2012). Leading man Hideaki Itô who played Hasumi in the film was also the star of the prequel, Miike however did not direct. It should also go without saying that in a filmography already filled with staggeringly audacious films, Lesson of the Evil is nonetheless one of Miike’s most brazen cinematic smacks in the face due to the film being made in an age where mass and school shootings are more or less a monthly occurrence so its really no surprise that a film featuring a teacher turning a shotgun on high school students wasn’t going to go down so well with certain people. Not to mention that the film also incorporates both homo and heterosexual relationships between teachers and students and Miike gleefully injecting his macabre comedic sensibilities into some of the more violent proceedings. Not that it mattered much to Miike. After all, he’s never exactly been one to cater to the hypersensitive needs of politically correct zealots. Given the cultural climate where said PC zealots run rampant in various forms of art, a film like Lesson of the Evil is gift and further proof that when it comes to cinematic transgressions, Miike is still one of the reigning kings.